Jakarta (ANTARA) - Sugar-coated it may be, but even when a teacher tells girl students how amazing they are on doing detailed work being the class secretary, there is all likelihood they won't ever be chosen class leader.

“For three years, they have been through voting processes some six times and the elected one in Kim Ji-young’s class is always a boy student.”

“Many teachers choose five or six girl students to back them for doing certain tasks including writing a score or to check everyone’s homework. They often say that girls are smarter.”

“Other students also think their girl classmates are more diligent, calm and conscientious. Yet when it comes to choosing the leader, they will go for the boys.”

Cho Nam-joo, a South Korean author who writes the story of “Kim Ji-young, Born in 1982”, captures the moment of inequality girl students face inside the education system in the country.

This, however, is only a fraction of the whole story of Kim Ji-young's life since she was a child until her 30's, which most likely tells us that this Korean woman lived in confusion over a patriarchal society.

Inequality becomes a common feature of patriarchy, where men hold the dominant roles in society within their own "manpower" as well as social privileges and political opportunities that place women in an inferior position.

UN Women, the United Nations' entity for gender equality and women empowerment, has launched "I am Generation Equality: Realizing Women's Rights" for this 2020 global theme of International Women's Day, celebrated on March 8.

The issue of equality had been discussed at the Fourth World Conference on Women in 1995 which resulted in the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, that UN Women said was a progressive roadmap for gender equality.

And now, "it's time to take stock of progress and bridge the gaps that remain through bold, decisive actions," the entity writes on its official website, that could show the meaning of solidarity to strive for equality, also of never-ending problems rooted in our societies across the globe.

Particularly in Asian communities, as mentioned earlier, Nam-joo pours out her thoughts as well as life’s reflection of women who surround her in the novel published in 2016.

"Sometimes, I think that Kim Ji-young is not a fictional character as she resembles my girlfriends, my senior and junior colleagues, and even myself," the author admitted, quoting from the book's preface.

The main character, Kim Ji-young, was born a girl when her parents were expecting a son. The parents' premise which was sourced from grandparents – was very illogical – that a son would provide a better living because only men can afford a lot of money and achieve higher social status, according to Nam-joo.

Kim Ji-young gets through many misogynistic events and institutional oppressions during her life in the family, school, social neighborhood, working environment, and even reaching the culmination point when she builds her own family.

"Actually in this book, Kim Ji-young seems to be very depressed and pathetic. But I know that she has grown up that way, live her life that way, since there is no other way. I've been experiencing it on my own," Nam-joo noted.

Around 20 years before the story of Kim Ji-young, in 1997, an Indian writer, Arundhati Roy, published her debut novel of "The God of Small Things", which mirrored the complex life of a big, honored family in a small village in her country.

The phrase "Small Things" at its title refers to many minor things that usually slipped out of people's concern.

However, compared with Nam-joo's Kim Ji-young has a simple yet meaningful storyline, Roy's writing is more likely complicated as she plays on some issues she is striving for, including gender and sexuality linked to traditional beliefs as well as social classes.

The girl-boy twin siblings, Rahel and Estha, are prominent characters here that should have struggled with their sexuality during life journey from when they were kids to being grownup.

Gender-based violence is carried out by their grandfather Papachi on his wife, Mamachi, over domestic issues regularly. Their Oxford-alumni uncle, Chacko, is vocal in expressing gender equality, yet manipulates his female employees and sleeps with them.

The fact that gender equality is included – or has a broader range –to other issues could be perfectly captured here in this book without setting aside the rooted value in Indian society that makes it possibly happen.

These two writers, Cho Nam-joo and Arundhati Roy, come from different backgrounds, traditional customs within each typical feature of South Korea and India.

But one connecting line of their writings is that inequality, especially on gender, is a threat for human beings. It could put women as the most aggrieved, yet also constrain men to always be perfect and bear more responsibilities according to society's demands.

Capturing the gender inequality through Asian writers' eyes

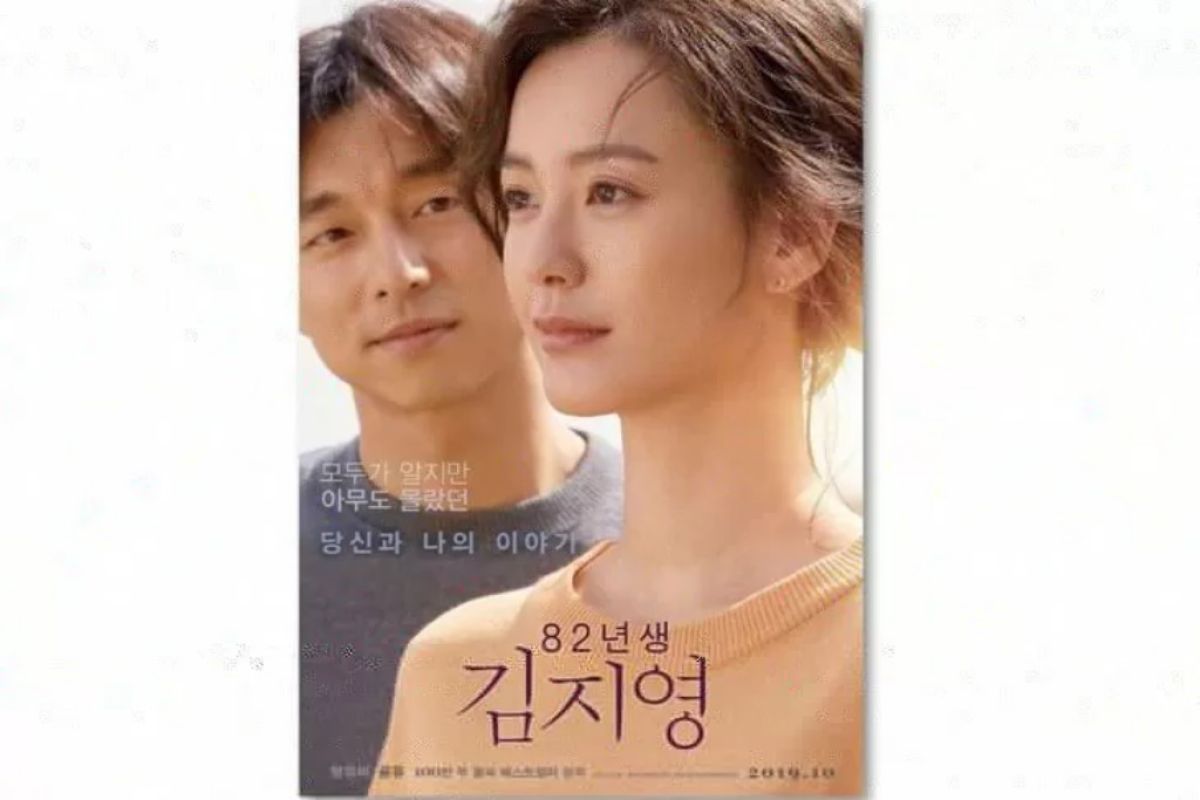

The film "Kim Ji-young, Born in 1982" is based on Cho Nam-joo’s bestselling novel. (ANTARA News/Instagram)